I’m very honored to have been short-listed for The Butterfly Awards in the category of author/blogger. The Butterfly Awards is an annual dinner in Great Britain to raise awareness for pregnancy and infant loss.

You can read my statement below. It’s the same statement that appears on the Butterfly Awards’ webpage — but on this page, I’m able to present it with images. You can click directly on the images to enlarge them.

If you’d like to cast your vote for the “people’s choice,” please visit my page on the Butterfly Awards website. Voting will begin after September 15. While you’re on their site, take a look at some of the other finalists for author/blogger as well as the other categories — there’s a lot of wonderful work being done out there!

And now, my statement:

The morning after we came home from the hospital, I woke with a start, expecting to feel Thor kick. Instead, I found the loose, wrinkled folds of my collapsed belly. I reached for a piece of paper and a pen and wrote. “11/13/08 6:30 a.m. I wake expecting to feel Thor kick.” Over the next days, weeks, months, a flood of words came out. I grasped my little booklet as I went from home to funeral parlor, park to cemetery, kitchen to living room. Torrents of words. I had never so much as kept a journal before.

These lines are from my memoir, Ghostbelly. With the gallows humor I developed after Thor’s death — don’t we all develop a bit of gallows humor? — I sometimes quipped that people deal with grief in one of four ways: They pray, they see their therapist, they self-medicate, or they make art. I couldn’t have guessed ahead of time which I’d do. None of them were my habit.

But starting at 6:30 the morning after I returned from the hospital, I made art.

I wrote before my stillbirth. But I wasn’t a writer. I was a scholar: an historian whose means of dissemination was the written word. I loved being in the archives, doing research. The writing part was like pulling teeth.

Thor’s birth and death changed all that. In the months following the stillbirth, words poured out. A different kind of words.

I don’t know where that creativity came from. Writing helped me to fill the time. I was supposed to be taking care of a baby, nursing him, rocking him to sleep. Writing gave me something more meaningful to do than grading papers or picking up groceries. It enabled me to give Thor a presence in the world.

But those were convenient side effects of writing. I couldn’t have willed myself to write in order to have a meaningful pastime or to give Thor a presence in the world — any more than I could have willed myself to sculpt or to write an opera.

Still, when I hear writers say, “My book is my baby,” I laugh a little to myself. They don’t know the half of it.

Ghostbelly describes experiences we’ve all shared, those of us who are involved in some way with the Butterfly Awards. The existential unease that comes from having a child who sits on the boundary between having-been and not-yet-having-been. The anger that the rest of the world goes on — it just goes on! — when it should have stopped in its tracks.

And the book describes experiences that not all of us shared. Taking my baby home for overnight stays and walks in the garden between his death and his burial. Confronting public accusations, and self-doubt, following a death in a homebirth setting. Parenting a high school senior, the result of an earlier relationship with a woman, while grieving the death of my newborn.

One of the first moments to give me hope after Thor’s death was reading an online commentary to an essay I published on salon.com. I don’t usually recommend reading online comments: it’s a quick way to lose your faith in humanity. But on one otherwise gloomy day, I heard from a reader who said that before reading my essay, he would have said that someone who spent time with her dead baby was sick. Now he got it.

Along the way, I gained more and more personal contact with bereaved parents, with grief professionals, with midwives and doulas who wanted to better serve their clients when disaster struck. I gave public readings. I discussed stillbirth at conferences. I corresponded with people who reached me through my Ghostbelly website. I participated in webinars for social workers and doulas who had read my book for a course.

I led workshops on writing through grief. They usually ended up with a roomful of people in tears. But the good kind of tears. The kind that people shed when they’re finally able to be honest about their pain in a room full of people who understand.

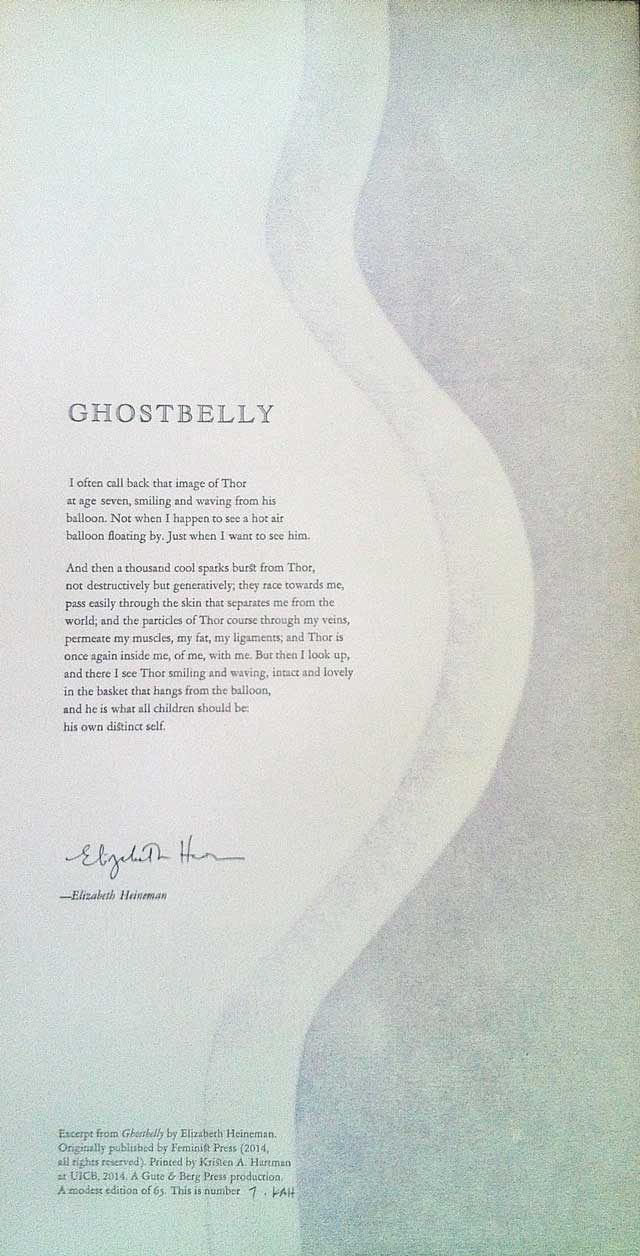

And along the way, Thor inspired more and more art. Thor’s older brother painted his casket lid. Then he made a short animated film about Thor. A voice actor created an audiobook of Ghostbelly. Thor’s grandfather wrote a poem. A student in my university’s bookmaking program made a limited-run letterpress — that’s printing the old-fashioned way, with hand-set inked letters pressed against a roll of paper — with her own art and an excerpt from Ghostbelly.

Then there was Jen Silverman. Brilliant, edgy Jen, a student at my university’s playwriting workshop, young enough to be my child but with the wisdom of an old woman. We talked about Thor over coffee, over cakes, while walking along the river. We talked about queer families, the relationship between the living and the dead, how different cultures deal with grief. She read my writings. And then she wrote a play, Still. It won the Yale Drama Series Prize.

Still is not a theatrical adaptation of Ghostbelly — at least, I don’t remember writing a book about a dead baby who befriends a pregnant 18-year-old dominatrix while wandering through town seeking his mother, who has holed herself up in her basement caressing a pumpkin and eating bad casserole. I told Jen that I didn’t need her to tell my story. I could do that myself. Instead, she told a story that aches with truth and heartbreak by making sure the audience knows and loves and — most importantly — will never forget the baby.

I see the play, I hear readers’ responses to Ghostbelly, I learn of midwives and doulas who have adopted new practices after reading about Thor, I see all the other art and conversations Thor has inspired, and I realize:

My baby is growing up. He’s out there doing things I never could have imagined for him.

He’s living his life.

Ghostbelly is by far the most beautifully written and intimate account of something a lot of us have gone through, which is the death of an unborn child. It’s an incredible and moving book, and I’m so thankful for it.

Jane Pratt, founding editor of xoJane and Sassy